It’s been a while since I’ve posted, I know. Today will be another post not about apples, but with them on the periphery- and that’s probably going to be more of the case moving forward. So, with that, here’s an essay on traditional osage orange hedges – the barriers, the planting and the management.

Background Intro of how I discovered osage orange, comparable to the preamble of a recipe website:

Back in 2016? 2015? I can’t even remember, I went on a wild cider drinking/apple exploring mission from VA to NC to AL and GA with Pete Halupka. We visited all the Southern apple greats, Tom Burford, Lee Calhoun, Joyce Neighbors and Jim Lawson to glean as much wisdom as we could in the realm of fruit exploring, growing and propagating. The unexpected twist of this trip happened when Jim Lawson shared that he had sold thousands of old grafted trees to some brothers in Georgia who planted them all over a small mountain/large hill, and had heard that the lower slopes of this mountain were covered in seedling apples from this original planting. Enamored with the idea of basically finding a 2nd generation Southern apple seed orchard, we set out to find it. And struck out. Turns out, a megachurch bought the property and had long done away with the trees. Feeling rejected, we went to the church’s coffee shop to get a coffee because that was the closest thing to a pick-me-up snack we could find. And that’s when magic happened…

It was probably 1pm and we were the only ones in this coffee shop, so we chatted with the guy behind the counter, who was a youth minister with passion for seemingly two things: coffee and Jesus. We told him our mission to find this wild seedling apple orchard and how we came so far only to discover that it was cut down. He then said: “You know, there’s an old estate near to here that was traditionally known for its peaches and peach brandy, but they might have apples! It’s called Barnsley Gardens. I’ll connect you with my contact there, she goes by the name Fairy Godmother.”

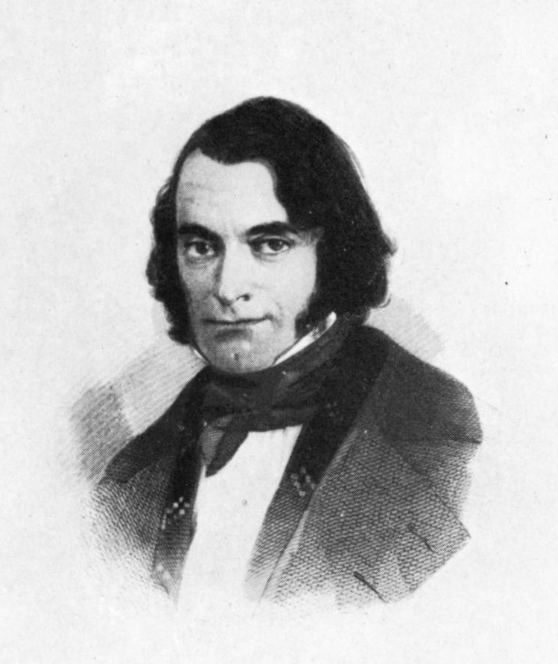

Some due diligence was needed to make sure that going to see the Fairy Godmother wasn’t code for showing up to a Baptist revival, after all we were in a megachurch coffee shop. And after some quick cell phone research, we discovered that Barnsley Gardens contained a different kind of revival… a gothic revival…designed by none other than the young prodigy Andrew Jackson Downing! For those of you who might not know, AJD was a prominent 19th century author, landscape architect and horticulturalist who, with his brother Charles, did much to advance fruit tree culture in the US during his short time on earth. We immediately and excitedly hopped in the car to go meet this Fairy Godmother.

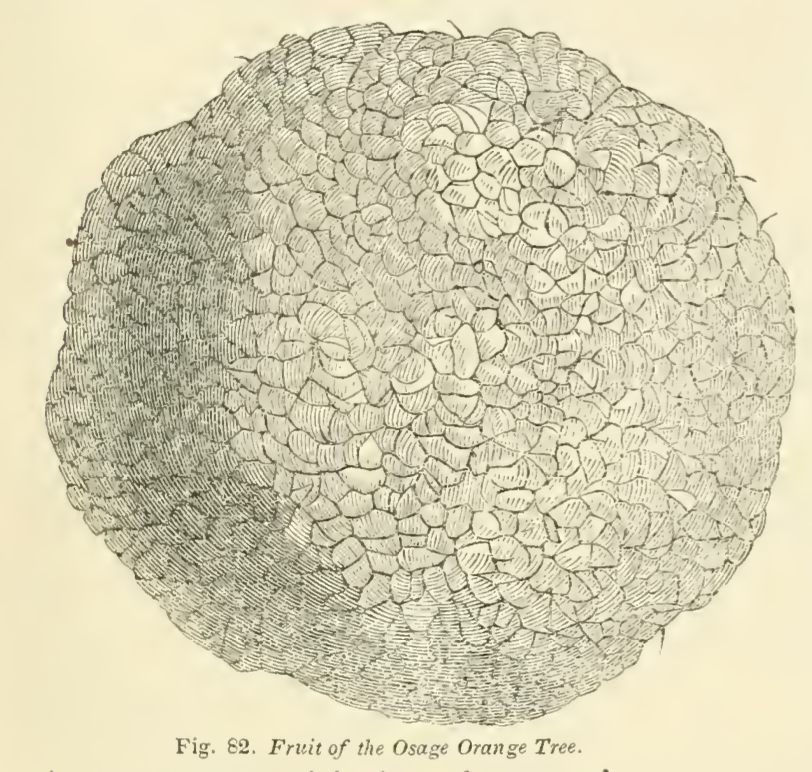

Rather than talk about how much booze the Fairy Godmother fed us once we got there, or her red sparkly kitten healed shoes, or the forest of seedling peaches and ancient muscadine vines, there was another aspect to Barnsley Gardens that is stuck in my mind. Driving through the former estate/now elite vacation destination, one of the roads was lined with very old Osage Orange (Maclura pomifera) trees. Loads of them. I’d never seen anything like that before and wondered why someone would plant so many of these trees along a road. Osage orange, or hedge apple, isn’t really something you study much in forestry school, and since they don’t produce commercial crops of fruit, I had never spent much time thinking about them. So, I filed this day and the road lined with osage trees away for years until a new client contacted me wanting to find out how to recreate the traditional living osage-orange hedge. This was my opportunity to do the deep dive, one of my favorite activities.

The American Osage Orange Hedge

When I had been tagged to do this deep dive, I had been living in Northern Virginia for a few years and had acquainted myself with some of the old 18th and early 19th century Quaker farms in the area. Over the years in this area, I noticed that old osage orange trees grew in lines in pastures and in woodlands. I knew, given their other name of hedge apple, that they must have once been part of an old hedgerow/fence system, but the questioned remained: How did farmers turn these trees into hedgerows? And where were they getting their information?

For hundreds of years post colonization (and even today), the goal of many wealthy landowners was/is to have a landscape that mimics the English garden and countryside. One aspect of the English countryside that many people wanted to implement in the 18th and 19th centuries in order to keep livestock in (or out) of their property was that of the thorn-hedge, which was overwhelmingly constructed of English hawthorn in its home country. The problem with using this in the US was that the English hawthorn, an apple cousin, doesn’t like the heat, humidity or fireblight pressure of the Southeastern/Mid-Atlantic climate. When the American hawthorn was tried in its place, people soon found out that when planted densely in a hedge, it would get absolutely hammered by the apple borer. Other thorny plants were tried in its place, such as honeylocust (Jefferson planted juniper with honeylocust and trimmed them to 3 feet tall)- which did not keep pigs out or in, while others trialed trifoliate orange-which never grew tall enough, and the imported buckthorn- which did great in the Northeast (now loathed for how well it did) but underperformed in the South.

It wasn’t until Lewis (of Lewis and Clark) sent osage orange seedlings from the Osage tribe in Missouri to Jefferson (who then gave them to the Landreth Seed Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) for this tree to slowly start taking root in the East. 30 years later, a young Andrew Jackson Downing, noticing this tree on the grounds of the Landreth Seed Company, soon became it’s greatest champion.

Andrew Jackson Downing: American Hedge-Master

When you start to dig deep into a landscape’s history, you may find relics of horticultural history hiding in plain sight. I now believe that the old osage orange trees growing in lines throughout pastures, woodlands, and alongside old roads are a remnant of Andrew Jackson Downing’s passion for employing this tree as a hedge and getting loads of influential early adopters on board in order to make this tree more accessible/affordable throughout the nursery trade. It has it all. Robust, thorns, vigor, glossy orange-tree like foliage, few insect problems, long-lived, can take a rough and severe pruning, and grows in lots of different soil types. Who wouldn’t get on board?!

In 1847, AJD was the editor of The Horticulturalist, and wrote a chapter on American hedges (volume 1, no. 8). It’s a great read and is also the only thorough explanation I’ve been able to find of how osage (in the South) and buckthorn (in the North) were propagated, planted and cultivated to produce an “everlasting fence.” Everyone who talked about osage hedges referred back to Downing’s work, so it does seem like he was the one to instigate the development of this plant as a hedge.

The large, wizened trees that remain today are the most successful trees in these hedges. Over the last 150+ years, combined with changes in fencing materials and land use, they’ve outcompeted/shaded out their counterparts in order to become single trees in a line. And these are the lucky ones. Though there is no turning back the time on these trees and transitioning them back into a hedgerow (you’d need to plant new trees), their canopies now provide valuable shade to livestock and their hollowed trunks are ecological hideouts for all sorts of critters. The picture below is one of the more visually intact relics of the osage orange hedge for keeping livestock out of the orchard/garden. Most are far more overgrown than this and have lost that first layer. It’s located in Frederick, MD.

The second iteration of Osage Orange Plantings:

About 90 years later, FDR through the Works Progress Administration planted osage orange throughout the Midwest for windbreaks to reduce soil erosion. Millions of them. These were not managed in the same way I’m going to describe below, so if you are in a Midwestern state and have a line of osage, it’s probably best to assume they were planted during this era.

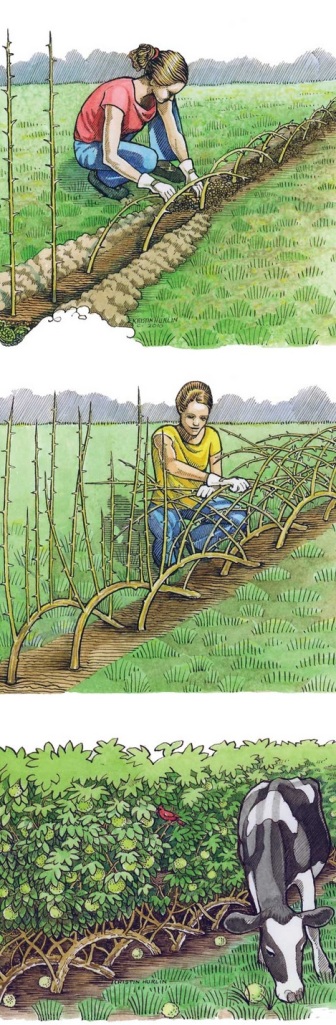

Also, it’s worth being said that many outlets back in the 19th century will complain how osage orange hedgerows to keep out livestock are failing because they were shoddily planted (plants in poor health, spaced too far apart, not cut back) and not managed the way they were meant to be managed. That correct way is what I’m laying out for you below for livestock fencing. It’s crazy to see various photos from permaculture sites showing cartoons of how to grow an osage orange hedge to keep out livestock, and the number of modern media sites referencing these cartoons.

HOW TO DO IT

Osage propagation:

From seed: Fruits should be gathered in the latter half of September. It should then be cleaned and stored in equal parts sand in a cool spot. A quart of sand/seed will usually produce around 5000 plants. Rather than seeding in place in the field, it is recommended that this seed go into a nursery for a year.

From root: Select root pieces that are the thickness of your pinky finger and cut them to be 3-4 inches long, with the top end being a flush cut and the bottom end being a diagonal cut (so you can tell the top from the bottom). Plant these cuttings in your nursery for another year so they turn into seedling trees. Plant the cuttings with the diagonal side down so the flush cut is just below the soil’s surface. These will push out vigorous shoots once the soil warms up enough. It’s easiest to take root cuttings off of new plants that were seeded in the nursery the year before. The root trimmings of 100 new plants in the nursery should produce 1000 root cuttings to plant out into the field.

Prep and Planting Out:

Site prep- In the South, this was usually done in the fall. The final width of this hedge should be 4 feet, so I would first take a subsoiler/single shank and rip your line down to 18 inches if you can. Then go over 6 inches or so and do it again. Then I would cultivate a 4′ swath, with your two ripped lines being in the center, with whatever you might have to break up the soil- tiller, spader- etc and cover crop it. In late winter/early spring (in the South), till the cover crop in again and dig your plants out of the nursery.

Spacing- For the first row, you’ll want to space each plant 1 foot apart within the row. For the second row, offset by 6 inches and then begin planting your trees a foot apart so it looks like this:

Immediately after you plant, while your plants are still dormant, you’re going to cut each plant down to 1 inch (or less) above the soil surface. This is to encourage multiple shoots of regrowth and lots of vigor once the trees break dormancy. You’ll also want to keep this as weed free as you can for the next 2 years in order to target as much vegetative growth as possible. This can be done in a variety of ways, from mulching to herbicide to cultivating.

Pruning Schedule:

One Year after Planting- While still dormant, cut the whole hedge down to 6 inches

Two Years after Planting- While still dormant, cut the regrowth of the hedge down to 18 inches in height (so keep the initial 6 inches from the previous year’s cut, and then cut everything above 1 foot of the most recent year’s growth, leaving 18 inches of total hedge height).

Three Years after Planting- While still dormant, calculate 1 foot of growth from the most recent year and cut everything above it. This will make your hedge a total of 2.5 feet tall, or 30 inches tall.

Repeat cutting 1 foot off the most recent years growth in pruning season until you’ve reached 5 feet in height (should be 5 years after planting). The base of the hedge should now be around 3′ wide and absolutely impenetrable, and the hedge’s width will taper as the height increases. This is where most people stop for cattle, however you can go higher for additional shelter or protection. Some people went as high as 10-12 feet.

When the hedge has achieved its final height and width, you’ll need to shape it 2 times a year with hedge trimmers: Once in June, the second in late September.

Here’s a GIF I made to explain it in picture form:

So did I implement this for the client? The answer is no, unfortunately. A hedge like this, whether in a pasture or elsewhere, needs protection from livestock and deer until the top is above the browse line. So in order to build a hedge like this, you’d need to protect it in the first 6 years with a fence on either side. This could potentially happen more affordably with with electric fencing on either side, but ultimately the deer pressure is so high here that electric fencing may not have worked. Osage orange is in the mulberry family and one of the favorite leaves of deer as is. However, one day I hope to do a small version of these hedges at my house. Can you imagine a 12′ osage orange wall/ deer fence? That’s the dream.

Thanks Eliza. Interesting how L & C brought OO back from the West.

There’s a long line of it on Wye Island near my old farm.

>