I’m a lifelong student of pruning. I LOVE learning, observing, and theorizing over tree physiology and applying newfound thoughts and theories with curiosity and gratitude every pruning season. Earlier this week, I saw yet another article talking negatively about heart rot, which motivated me to finally finish my essay on the subject. In this essay I’ll talk positively about heart rot, tree physiology, pruning and orchard ecology.

“That’s heart rot. The tree’s health is in decline” replied one horticulturalist to the above photo. “Hey, that’s heart rot…you had better apply a fungicide spray” replied someone else. And my response? Have you ever pruned an old tree?!

When it comes to pruning, I almost exclusively work with old trees and I see this a lot. Yes, it’s heart rot. No, I do not believe this tree is in imminent danger or even in decline, which is surprisingly a stance that not many people take. And so we’ll start there.

What is heart rot?

Heart rot is what happens when the pith of a tree (the center) starts to decay. The instigators of this core decay are fungi that get into the heartwood through wounds, broken branches, pruning cuts, etc. In a healthy tree, they only stay in the heartwood, which is the part of the tree that is not considered alive. It is often thought of as the dumping grounds for the tree, where minerals and older tree rings go to rest.

As fungi gradually work their way through the heartwood, the tree becomes hollow over time. In the timber realm, these fungi are considered harmful pathogens because they reduce the value of a log. Hollow logs= less money. This way of thinking, that fungi are harmful pathogens and hollow is unsaleable, somehow worked its way into horticulture, only this time… Fungi= harmful, Hollow=structurally unsound/sick/dying. So very rarely have I seen someone in the horticultural realm step back on the subject of heart rot to see the forest for the trees, which is why I’m writing this essay.

What is heart rot doing to the tree?

Way back in 2007, when I was doing a lot of forest inventory in Louisiana, I had to core all sorts of trees in order to assess their health and age. Often, after removing the core, I’d get sprayed with stinky water, spurted with methane from the hole I created, or witness a mass evacuation of insects. Lots of life inhabited those trees and that’s because heart rot fungi slowly made way for life to be there. This concept of rot-makes-habitat was really hammered home when I helped a USDA sniper tranq some inbreeding black bears that had chosen to calve in the cavities of old cypress trees. Straight up Winnie-the-Pooh habitat, those cypress swamps. Only poor Winnie was shacking up with his cousin in this scenario and had to move.

Fast forward 11 years to 2018, when I flew to Basque France to attend a conference on pollarding. It was there, surrounded by European foresters, forest engineers and horticulturalists, that everyone had a special place in their soul for heart rot and hollow trees, something I had never encountered before. A prevailing opinion, which I now view as a bridge between forest ecology and horticulture, was that heart rot creates hollows/habitats for all sorts of fauna. In hosting this fauna, the trees become collectors of poo (feces, not the bear). This creates an incredible microbial metabolism in the tree which, when combined with decomposing heartwood full of trapped minerals, supplies a steady amount of organic fertilizer that is slowly released to the base of the tree. Since trees store growth rings in the heartwood on an annual basis, this natural process of decomposition and fertilizing is a renewable. Hollow trees provide their own compost. That’s true sustainability.

WWW.HOGTREE.COM

But isn’t a hollow tree a weakened tree?

The comparison I always see is that heart rot or hollowing makes the tree structurally unsound. I’m here to tell you that this is mostly an emotional reaction. In all reality (and some physics), the tree isn’t weakened at all until the trunk’s radius is 70% hollow1.

And keep in mind, that’s an un-pruned forest tree with a full crown. If the tree is pruned to allow for airflow and to correct for weight imbalances, the hollow tree is much more structurally sound. An old pollarded willow tree, for example, boasts complete structural soundness until the trunk’s radius is 93% hollow2 thanks to a radically reduced crown . This tells me that mostly hollow orchard trees (on good root systems. Eff dwarfing trees), if pruned regularly, pose very little structural threat.

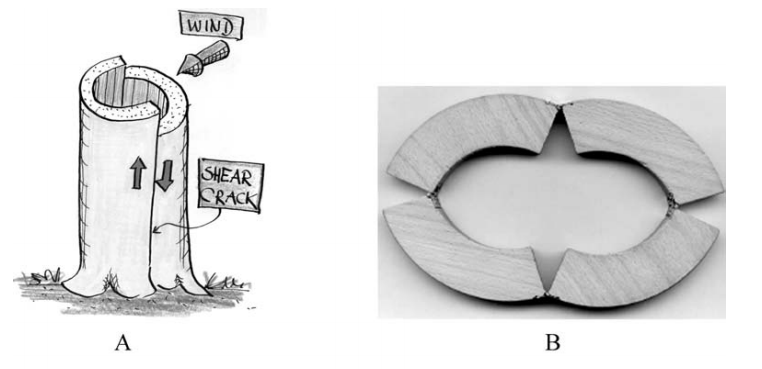

What causes a hollow tree to ultimately fail?

When trees are hollow and the wind has a strong influence over them (most likely due to crown size and density), the circular trunk becomes a bit oblong. This creates a vertical crack, which is the ultimate shearing stress for the tree. Again, pruning for crown reduction in old trees really helps to avoid the development of these shear cracks.

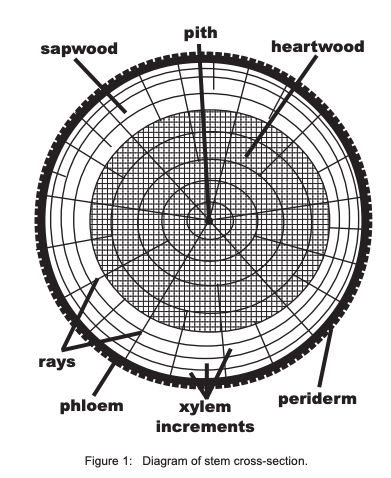

More explained through tree physiology.

Here’s the deal. Trees contain both sapwood and heartwood (see tree cross section picture at beginning of essay). The sapwood is the outer, living, layer of the tree that is responsible for carrying water and nutrients up to the canopy. Think of it as a bunch of tubes, or vessels (xylem), constituting the lifeline of the tree. Since this is one of the most important parts of the tree, it’s a heavy consumer of photosynthetic energy and a lot of that energy is spent on defense against pathogens (like fungi and bacteria) entering into this important area of transport.

If the sapwood is injured, the tree has an incredible and diverse defense process. One defense in particular that is easy to conceptualize is when tissues (parenchyma) outside of the vessels (xylem) cauterize the wounded vessels and separate them from sound vessels. In Malus, wounded vessels get plugged with a starchy-watery gum that is aptly named “vessel plug.” Other trees have tyloses instead of gum, and when the vessel (xylem) is injured, the parenchyma tissue grows into the cut chamber to seal it off3 .

I’m telling you about vessel plugs only to hammer home the point that sapwood has a lot of defenses that work tirelessly to keep invaders, whether from an accident or from decomposing heartwood, away from their life-transport network. This is part of the reason why maintaining a youthful vigor in a tree is important, because younger wood contains a higher ratio of sapwood to heartwood, increasing the defense capabilities of a tree on a minimal energy budget.

The higher ratio of sapwood to heartwood is also why it is better to prune younger wood on fruit trees. When pruning, the wound is much more efficiently cauterized and uses less energy.

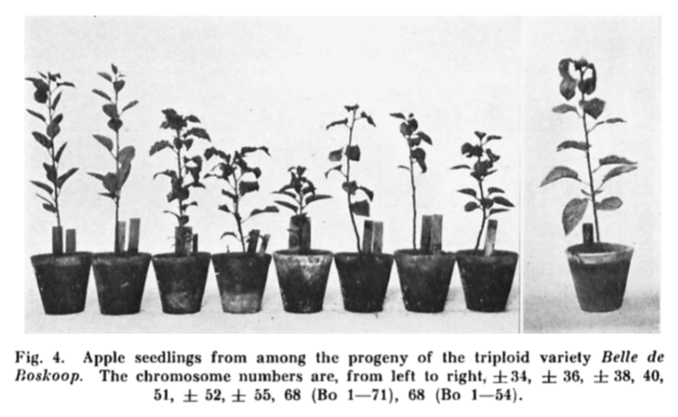

I’ll also note that the ability to cauterize, or create fast boundaries to some sort of attack, is often genetic. Look no further than fireblight tolerance in a durable apple like the Dula Beauty (triploid) compared to the sickly Esopus Spitzenburg to get a better idea of the genetic range.

Pruning larger limbs.

When I consider pruning larger limbs, the rule of thumb for me, unless a giant intervention needs to happen or I’m topworking (grafting in place), is that I often don’t cut limbs larger than 4 inches in diameter. This is strictly something I do in considering the tree’s energy. If the ratio of sapwood to heartwood goes down with age, then it takes a lot more photosynthetic energy (that starch-water mixture) to plug up a larger wound on an apple than it would a smaller wound. Add that energy expense to the tree simultaneously trying to activate dormant buds to create new growth, and even I’m exhausted. Let me be clear, though. I’m not doing this to protect from heart rot, which costs the tree relatively little energy. I’m doing this to help the tree balance its defense and growth energy.

Hollow trees in the orchard: Mycorrhizae

If you believe that hollow trees create their own compost and self-fertilize, and if you believe that pruning trees is a way to make hollow trees more stable, then let’s briefly mention mycorrhizae.

Mycorrhizae is the fungal network that is known to connect trees to other trees and allow them to talk and share resources. They connect trees to other resources by having their hyphae (or the fungal threads of mycorrhizae) grow in and around the tree roots. The roots release sugary exudates, which feed the hyphae and give them energy to go mingle. What causes a tree to release sugary root exudates? Pruning is one way, because tree branches are connected to tree roots. Once you start pruning a tree, the fine root system connected to those branches will die back. It’s not a 1:1 prune: root dieback ratio, as the root system is larger than the crown, but there is for sure some dieback.

What’s more interesting to me, however, is the confluence of fine root dieback from pruning, plant-microbe interactions from a hollowed out trunk and fungal hyphae in the soil. It’s a bit like Captain Planet; when these three powers combine, nutrient uptake and overall ecosystem health are enhanced. And this is why I’m on team ‘hollow tree.’ It’s almost as if the tree is creating it’s own “edge,” or diverse environment in which it and everything around it thrives in a wild and chaotic balance.

Final Comments (for now):

Instead of viewing hollows as condos for pathogens, view them as beneficial habitats that improve your orchard ecology. They are important refuges for all sorts of critters, from insects to birds, microbes to fungi, and maybe even a black bear (just kidding). Given how important these hollows are, NEVER! and I repeat, NEVER! Fill those holes up with concrete or bricks or anything else. Not only does it royally piss me off to ruin a chainsaw chain to some branch that was filled with concrete, but it’s not helping the tree in any way. And would you want to come home one day only to find your house filled with concrete? No.

Let’s keep an open mind to heart rot, ok? It’s performing a pretty amazing ecosystem service with no inputs from me.

NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO!

Citations:

1.) Mattheck, C., Bethge, K., & Tesari, I. (2006). Shear effects on failure of hollow trees. Trees, 20(3), 329–333.

2.) Wessolly L, Erb M (1998) Handbuch der Baumstatik und Baumkontrolle, Patzer Verlag

3.) Bonsen, K. J. M., & Bucher, H. P. (1991). WHAT ARBORISTS HAVE TO KNOW ABOUT VESSEL PLUGS. Arboricultural Journal, 15(1), 13–17.

Know anyone who might want to sell a farm somewhere in the Eastern half of VA. I’m looking. Click here.