One of the most important considerations to me when growing apples in the South is if the cultivar has a tolerance to pests and diseases. Called “the final frontier” by my Northern and Western apple growing friends, the Mid-Atlantic and the rest of the US South are notoriously difficult areas to grow domesticated fruit. In true Southern hospitality, our soupy humidity and hot temperatures not only extend a warm embrace to all sorts of pest and disease here, but invite them to stay for a long while and breed.

Despite this high diversity of fungal, bacterial and insect pressure, there are still old apple trees in the landscape that have survived decades upon decades of environmental assault. These trees have been the subject and target of much interest in my network of fruit explorers, as these specimens are proof that it is possible to grow purposeful fruit and trees in this landscape without toxic, self-perpetuating inputs. In past essays, I’ve discussed rootstocks being a factor in this, where larger root systems tended to produce healthier trees. But there are more factors in resilience than just the root system. In today’s essay, which has literally been in my drafts for 3 years, I want to discuss something I’ve been casually studying for years: Polyploidy, or having more than 2 paired sets of chromosomes.

I’ll begin with a bit of history. In the early 1900s, there was a Swedish plant breeder and geneticist named Herman Nilsson-Ehle, who had spent much of his professorial career breeding wheat and oats for high yields in Sweden. He was a huge fan of Gregor Mendel, who had released his findings on inheritance only 8 years prior to Nilsson-Ehle’s birth, and his whole outlook on plant breeding research was a hat tip to Mendel. Mendel, for those of you who may be struggling to remember, was the Monk who stared at pea plants and developed the fundamental laws of inheritance, which we encountered in high school biology as the punnett square .

Before I go any further, I want to give a quick warning. From my research on Nilsson-Ehle, it appears he was a fan of “new Germany,” and saw the genetics research under Hitler’s regime as a means to save the world. In order to only showcase the apple breeding aspect of this man, I’m not going any further in this subject. If you want to read more on his thoughts, which scarily echo modern times, you can go here: Lundell 2016.

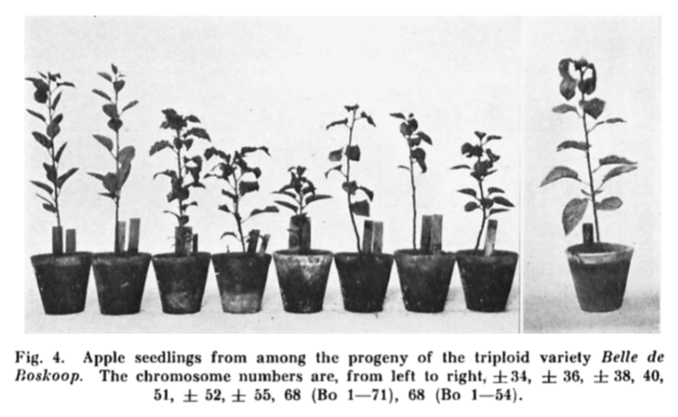

In his early research of breeding cereal crops, Nilsson-Ehle would sometimes observe natural mutations in the hundreds of thousands of seeds he planted out for observation. These mutations had much larger, rounder leaves and after poking and prodding these mutants, he discovered their large size was due to having 2 additional sets of chromosomes, or polyploidy (Usually a diploid (2 sets of chromosomes), these plants were now tetraploid (4 sets of chromosomes). These plants exhibited giantism in all ways aside from vigor (which was relatively low). While the leaves and shoots were much thicker than diploids (2 chromosomal pairs), the flowers, fruits and seeds were nearly double in size. This was remarkable to Nilsson-Ehle and prompted him to theorize: If I take this mutant tetraploid and cross it back with its diploid self from the same cultivar, I should get a triploid (3 sets of chromosomes) that brings about enhanced genetics of both!

He was right. The tetraploids he crossed with diploids produced triploids that were more vigorous, hardy and resistant to disease than their diploid or tetraploid counterparts due to enhanced genetic modifiers inherited from the parents of two different ploidy (tetraploid and diploid). This brings me back to fruit exploring in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern US. The large majority of US cultivars known today as being able to tolerate fireblight, apple scab, powdery mildew, and loads of other issues while still persisting in the Southern landscape for decades upon decades are triploids! Including the Dula Beauty, my sturdy family apple cultivar.

Support my writings and more through the purchase of charcuterie at www.hogtree.com

So the US picked up on Nilsson-Ehle’s breeding work and adopted it to their work in the states to breed for hardy, disease resistant apples, right? Nope. WW2 happened and we were already distracted with breeding for scab resistance (more about that in a bit). In 1950, famed berry breeder George Darrow reported on Nilsson-Ehle’s work in an address to the American Horticultural Society. In this address, he mentioned the premise behind Nilsson-Ehle’s work and connected the dots in how this way of thinking has translated into berry breeding for larger, higher quality cultivars. He briefly mentioned apples in this address, reporting that a tetraploid sport (mutant) of McIntosh had been found growing on branches of a normal McIntosh tree in New England, but the mutant branch was only half tetraploid, as the cortex of the wood was diploid (making it a ploidy chimera). He said they were trying to stabilize the McIntosh chimera as a full tetraploid through tissue culture, and I believe they achieved this due to the photo below. This was the end of an interest in sustainable fruit breeding in the US, in my grumpy opinion.

Come on, Eliza, what about the Liberty apple? Goldrush? RedFree? Prima? [Slight rant/history on apple scab. Skip to below scabby apple pic to avoid]. Sure, there was a breeding effort between selected US land grant universities (PRI= Purdue, Rutgers, Univ. of Illinois) that began in 1926 to create scab resistant apples. They succeeded in doing so in a basic sort of way, which eventually led to the downfall of this research. The style of their research was “monogenic,” or relying on a single gene to control scab resistance in an apple cultivar. There was also a whole lotta inbreeding going on.

The gene identified to have scab resistance is called the “vF gene,” which comes from the cultivar “Malus floribunda 821.” The reason why they picked this gene is because they could identify it in seedlings using molecular markers, so they didn’t have to waste time growing the trees to find out if it was scab susceptible or not. That worked out well enough for a while and they selected some ho-hum cultivars (minus Goldrush, which is awesome but incredibly prone to cedar apple rust) to make available to the public. In 2002, the first reports of scab infection were reported on the scab-resistant apple cultivar ‘Prima.’

In 2011, a German pomologist wrote an article about all of this and, thankfully, it was translated into English shortly thereafter. What he found, looking into the lineage of most US and Euro scab resistant apple cultivars, was a huge amount of inbreeding going on. Not only that, but the cultivars being crossed back to themselves were highly susceptible to scab! I’ll quote directly from the article:

“Today the global fruit breeding industry is producing a wide range of varieties, with one big difference: the overwhelming majority are descendants of just six apple cultivars.

The author’s analysis of five hundred commercial varieties developed since 1920, mainly Central European and American types, shows that most are descended from Golden Delicious, Cox’s Orange Pippin, Jonathan, McIntosh, Red Delicious or James Grieve. This means they have at least one of these apples in their family tree, as a parent, grandparent or great-grandparent…”

Many of the PRI releases have these 6 cultivars crossed multiple times in their lineage. If you do this right and bring out the right traits without problems, it’s called ‘line breeding’. If you end up with problems, it’s called ‘inbreeding’.

The second and main problem with this breeding work, in my opinion, was in our complacency with our selections. We basically ignored any further breeding efforts for scab resistance in order to pursue “Crisp” apples. Takeaway message: FEEL GUILTY ABOUT EATING A HONEYCRISP, COSMICCRISP, CRIMSONCRISP KARDASHIANCRISP ETC. BECAUSE THATS WHAT BREEDING LOOKS LIKE NOW INSTEAD OF BEING ABLE TO GROW APPLES WITHOUT MAJOR INPUTS! Too bad we haven’t been thinking about triploids or even multiple-gene scab control for the last 50 years.

Guess who has? Russia.

Since the early 80s, the All Russian Research Institute of Fruit Crop Breeding (VNIISPK) has continued with the scab resistant vF breeding work that spread across the US and Europe, only it is way more badass. Not only are they breeding for scab resistance, but they’re breeding for tolerance to late frosts, consistent yields without having to thin fruit, COLUMNAR growing habit AND Nilsson-Ehle’s version of triploidy (Speak a little more into my dirty ear, Russia). However, the near-sensationalism of these claims doesn’t stop there. Dr. Evgeny Sedov, the primary researcher in this endeavor (and someone I would really love to interview), closes the abstract of one of his scientific papers that goes into his triploidy research with the following that is so, so Russian:

“It is noted that triploid apple cultivars developed at VNIISPK are inferior to none of the foreign cultivars, based on a complex of commercial traits, and they significantly excel foreign cultivars in adaptability. Our apple cultivars may contribute to the import substitution of fruit production in Russia.”

Some mentioned and additional benefits of triploids (Or reasons to pursue more polyploidy breeding):

- Adaptability to climate, disease, stress: In the above quote, Sedov writes how his triploid apple cultivars significantly kick other apple cultivar ass in terms of adaptability. And based on my research covering the last 100 years, he’s not wrong. There have been many observations by the scientific and lay community reporting that triploids end up being more cold hardy, more heat tolerant (the thickness of leaves and fewer, larger stomata give rise to a lower transpiration rate and more water retention that can be used during drought), have better nutrient uptake, and improved resistance to insects and pathogens. The theory for triploids having a higher environmental adaptability has to do with an increased production of secondary metabolites, which enhance plant resistance and tolerance mechanisms (as well as chemical defense).

- Thinning: Triploids often have low fertility due to a reproductive barrier of having an extra set of chromosomes- making pollination difficult. Some apple pollen tends to pair decently well with triploid apples to get a decent crop. With most cultivars it isn’t great- just good. This could be seen as a boon to this class of ploidy, but I see it as a good thing. One of the greatest challenges to organic apple production is the thinning process. Most non-organic orchards thin using chemical sprays to knock off flowers or fruits. To this day, many organic spray chemicals either do a lackluster job, or oh-god-that’s-far-too-many-job of thinning the fruitlets off, leaving many orchardists to either thin by hand or accept biennalism (which was a 3 hour conversation at Stump Sprouts one year). If you have healthy pollinator populations, less fruit on the tree will guarantee you a return crop the next year, barring other environmental catastrophes (which you’re better prepared for with triploids, anyways).

- Vigor: In the past, I’ve written about vigor on the Elizapples.com blog and how it’s my number one enemy in the Mid-Atlantic given my heavy soils, warm temperatures and ample water supply. Though I need to revisit those essays and condense them into my current evolution of thought, the reason for my past concerns around vigor is that I have conditions that induce [what I’d like to think is] “artificial vigor.” In my climate, this shows up as extreme vegetative growth, which sometimes gives rise to heightened fireblight pressure and other vulnerabilities. Though “artificial vigor” is likely what an incompatibility of growing conditions looks like, I’ve started to differentiate it from what I’m calling “true vigor,” or youthfulness through heterosis/hybrid vigor. This is where triploids shine.

When you start digging in old texts, back before the rise of clonal rootstocks, you might encounter mention of two classes of trees referred to as “Standards” and “Fillers.” The “standards,” often mentioned as Baldwin and Rhode Island Greening (both triploids) were larger trees that took longer to bear fruit. These were thought to be permanent trees, or trees that would be around for generations. The “fillers,” such as Yellow Transparent and Wealthy, produce much smaller trees in the same length of time and were far more precocious in bearing fruit. These trees were thought to be temporary, and were planted in between the “standards” to increase production in the early life of the orchard. An unfortunate modern day “filler” would be HoneyCrisp (diploid). Growing in my climate, it is better termed runtycrisp. Super low vigor, gets loads of diseases, precocious bearer, dies early. Sort of an orchard mercenary. This, to me, is a good way to think about vigor. If you’re growing for the long-term, you’ll want a truly vigorous cultivar that teems with youthful energy, and I believe that youth is heightened as a triploid. If you are growing in areas that are full of pest and disease, it is also not a bad idea to have an extra set of chromosomes to help with defense and stress. Relic trees standing tall in the South tend to be triploid and their presence speaks to their youth and defense: Arkansas black. Fallawater. King David. Leathercoat. Roxbury Russet. Stayman Winesap.

With all of this said, we have a lot of work ahead of us to start thinking about what our breeding programs would look like if we set our targets on low-input, no spray, multi-gene disease tolerance and more. I get it, HoneyCrisp can store for a calendar year in my crisper drawer, but that’s all it has going for it after a year in there.

I am pulling for the expansion of ‘process’ industries such as hard cider, vinegar, juices, syrups, etc to become the targets of agroforestry planning and planting enterprises in the near future. Annual or livestock farmers don’t want to mess with sprays or inputs that are outside of their normal non-tree crops care. If they are going to receive incentives to plant trees on their farms, they will want the ones that need little care and have an economic outlet. This will require a new set of apple cultivars to choose from and they have to come from somewhere…

Here is an incomplete list of confirmed triploid apples. Many of these are from the UK and do so-so in my climate. The ones with asterisks are what I have seen as old relic trees in the Mid-Atlantic:

Arkansas Black*

Ashmeads Kernel*

Baldwin*

Belle De Boskoop

Blenheim Orange

Bramley’s Seedling

Buckingham*

Bulmers Norman

Canadian Reinette

Catshead

Close

Crimson Bramley

Crimson King

Crispin

Dula Beauty*

Fallawater*

Fall Pippin*

Frösåker

Genete Moyle

Golden Reinette von Blenheim

Gravenstein*

Hausmuetterchen

Hurlbut

Husmodersäpple

Jonagold

King David*

King of Tompkins County

Lady Finger

Leathercoat*

Margille

Morgan Sweet*

Mutsu

Orleans Reinette

Paragon*

Red Bietigheimer (Roter Stettiner)

Rhode Island Greening*

Ribston Pippin* (struggles with brown rot)

Roter Eiserapfel (Has 47 chromosomes rather than 51)

Rossvik

Roxbury Russett*

Shoëner Von Boskoop

Spigold

Stäfner Rosenapfel( Has 48 chromosomes)

Stark

Stayman*

Stayman Winesap*

Summer Rambo*

Suntan

Tom Putt

Transcendent Crab

Transparente Blanche

Vilberie

Vixin Crab

White Astrachan*

Winterzitronenapfel

Winter Pearmain

Washington Strawberry

Want to see more essays? My time can be compensated through the purchase of non-gmo, nitrate-free charcuterie at www.hogtree.com