I’ll begin this little essay about apples, but I’m going to end with oak trees. If you are interested in silvopasture, stick with me…

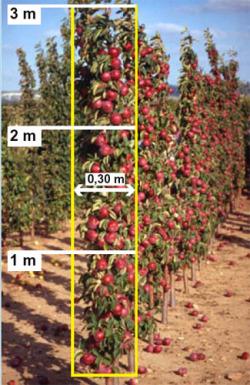

Back in the 80’s, there was a sport (genetic mutation) which occurred on a single McIntosh apple tree in the UK. This branch was different from all the others in that it was virtually free of side branches and STILL produced an edible fruit. The apple people started calling this sport a columnar or fastigiate apple, and it looks like this:

I originally learned about this kind of apple tree from Nick Botner, an apple/grape/pear/cherry/peach/etc curator in Oregon, who showed me the growth habits of his columnar collection. Once he showed me the spacing one can achieve with these apples and the form they take on, my mind took off.

I go back and forth on planting high density orchards. The numbers work out economically to grow high density if you have the start-up capital, and the pruning and harvesting time involved is hard to beat. But my problem is in the trees themselves. Grafted onto dwarfing rootstock, their small root balls are unable to mine the soil like a larger tree does and as a result, they require irrigation, fertilization and weed free strips in order to keep them producing like they should. Not to mention, I’m suspicious that apples produced by dwarfing trees don’t taste as good or have the nutrient density of the deeper rooted ones.

My thoughts for a few years now have circulated around: How can I grow a high density orchard more sustainably with less inputs? This columnar apple is an idea which could potentially address these thoughts. Theoretically, I could graft these trees to larger rootstocks (such as m111 or wild crab) and have them much closer together than otherwise possible in a regular orchard planting. On these larger rootstocks, they’d be able to fend for themselves and would require lower inputs. Right?

I’ve yet to try this due to funds, but I am actively seeking all columnar cultivars possible to try out in a nursery setting to see how they do…

Which leads me into how this blog article is going to transition into oaks. When google searching for columnar cultivars, I started including another search term which is used as a descriptor for upright growth: fastigiate. To my surprise, I learned of other fruit trees which possess a columnar nature; Peaches, pears, cherries… and even OAK TREES.

Before I launch into oak trees, let me be clear for a second and further spell out the meaning of a columnar tree because it matters. In the apple world with all of it’s new rootstock technology, it is known that more trees per acre produce more bushels of apples per acre…earlier (more precocious). This is why all sorts of orchards are converting over to high density plantings…because they are now able to maximize acre production. Now, why not apply this sort of orchard thinking to silvopasture?

Enter: Quercus robur ‘Fastigiata’ x Quercus bicolor(and other hybrids with ‘fastigiata’)

Once upon a time, an English Oak hybridized with a Swamp White Oak and produced this:

Do you know what this is?! THIS IS A 45 FOOT TALL TREE WITH A 15-20 FOOT SPREAD!!!

Do you know what this means? With this type of hybrid oak, there’s a real chance you could pack-in far more healthy oak trees than ever before onto an acre (or a hedge), all of which will produce acorns. Just like with apples, more trees pre acre likely means more bushels per acre.

In old (early 1900’s) articles I’ve read about oak cultivation, there were once oak trees called names like”Juicy Hog Biscuit” to indicate that these cultivars were grafted to pastures where hogs were fed from these trees. There were stories of oak trees which produced heavily and oak trees which produced annually*, and the TVA even started a project which ended up getting cancelled on oaks for livestock production. Yet, given the way of our agricultural history which has largely abandoned diversity, today we’re left trying to single out stellar cultivars and breed others. With a lack of these Juicy Hog Biscuit genetics in today’s time, could a hybrid oak possibility like this be the new feed lot where you can finish your pigs on more bushels per acre of acorns than previously thought possible? I’d like to think so. I mean, if we’re doing it with apples, why not oaks?

I’m chomping at the bit to do something like this for my pigs in the near future. Whether a hedge or a flat out orchard planting, we’ll see. Let’s put our heads together to see how we can better access these genetics and get moving on these trees. They are good in wet soils, dry soils, cold climates and warm climates. Please contact me with ideas and thoughts. Questions I have:

-What is the mast production like for these hybrids?

-Age to production?

-What happens if I top this tree? Will it still keep the columnar form?

This is also a reminder that further breeding needs to happen in order to make this form of agriculture competitive with corn. What if we crossed a specific white oak known for abundant acorn production with an English oak (var fastigiata), for example? We’re looking for the columnar shape which would likely make itself known early in the selection process. This is all very exciting to me and the potential is limitless.

*On a recent NNGA thread, Sandy Anagnostakis pointed out that many oaks could be annual bearers if the late frosts could be avoided.

This place has been sending me signals for a while. It is rich with Quaker horticultural history, which my fruit exploring team and I are uncovering one grafted tree at a time. We have found more

This place has been sending me signals for a while. It is rich with Quaker horticultural history, which my fruit exploring team and I are uncovering one grafted tree at a time. We have found more

Want to know how to convince young people that there are worthwhile careers in the tree fruit industry?

Want to know how to convince young people that there are worthwhile careers in the tree fruit industry?

_-_Vermont_Beauty.jpg)