A long time ago, orchard and nursery people often grafted scions from known cultivars onto dug-up root pieces from apple trees. This was one of the ways in which orchardists and nurserypeople were able to propagate specific varieties rather than getting something completely random from seed. The other way was to graft onto existing trees (called top-working, or top-grafting) or onto rootstock produced by planting seeds.

Root grafting (on purpose) has largely disappeared as a horticultural practice due to the rise of clonal rootstocks. We are now able to decide what size tree we want and how soon we’d like the tree to bear apples, which has been the primary cause for eliminating old “standard” sized trees from the landscape. In fact, you wouldn’t believe how many old orchards I visit where the owners have been told by the extension service to cut down the old orchard and plant high density apples…

It’s true that high density apple systems have proven themselves to make more money than trees able to stand up by themselves (in a high-input dessert fruit market), but I’m not totally sold on that model when it comes to growing process fruit for cider, pies, etc. I’ve run the numbers (which I’ll share soon) and you’d have to plant many, many acres of apples to make it work out financially (if you were to sell wholesale and not turn them into your own value-added products). After it’s all said and done, you’ve got an orchard that can live for 25 years on a spacing that makes it hard to “stack functions,” or grow other crops/animals within your system to have a diversified income (which is necessary for me)

*Disclaimer* I have heard from a smart orchardist outside of Pittsburg who is growing black raspberries on the same trellissing as his high density apples with wild success.

Back to root grafts:

- Yes, these trees are often times very large compared with apple trees grown on clonal rootstocks.

- Yes, they are going to take 10-10+ years to bear fruit.

- Yes you can only fit 55 trees per acre…

But…

- I’ve seen a lot of old apple trees in my lifetime, like the one pictured above which is over 200 years old! That tree was root grafted and, as a result, on it’s own roots.

- The Fruit Explorers, a group of which I’m a founding member (along with Pete Halupka of Harvest Roots Farm and Ferment), traveled around the South last year looking for all sorts of apple trees. By far, the healthiest trees we found were those on standard rootstock or growing on their own roots. We were in the hot, humid, zone 7a-8a South which is known for all sorts of rots, fireblight strikes, fungal infections…you name it. And the trees that looked the best were the big ones. All of this observation caused me to believe that we probably have the best chances of growing low-input trees if they are on big roots.

- I can grow other crops in the rows between the trees. I can graze animals. I can have a diversified income stream while waiting for the orchard to come into bearing and for the canopies to narrow the rows.

- The trees will be of uniform size if you are root grafting the same cultivars within the row

- Who’s to say these trees won’t each drop 100 bushels of apples a piece?

Basically, all of this is to say: I think that root grafting isn’t such a bad idea for an orchard if you have the space and the time. I’m crossing my fingers that I’ll have the space in the next couple years, so the remainder of this blog post is about my thoughts and actual practices of root grafting…

This year, I ordered 1000 southern crabapple trees from the Maryland State Nursery (Malus angustifolia). I decided on M. angustifolia because I’m in the South and these crabapples are better adapted to this hot and humid climate. Also, I had already decided that I wanted standard sized trees, so why not use them as a rootstock?

Well, after I ordered them I did some digging and realized that M. angustifolia, which on average is not that large of a mature tree (maybe 20 feet), would probably not be able to handle the vigor of the heirlooms and cider varieties I wanted to graft. Across the boards, from writings I found in the 1800s to anecdotal quips from friends and thoughts from mentors, it seems like the majority of these seedlings would only be able to handle the graft for a few years and then the top would eventually outgrow the bottom, resulting in death. The success stories I read involved topworking mature, already-in-the-ground-and producing-crabapple trees OR grafting onto crabapple stock from Russia. Russian crab stock is more vigorous and able to handle the older varieties and I’ve seen evidence of this in very old orchards in Maine, where the cultivar died out and the crab stock bolted upward.

Compared to the Siberian crabapple stock we ordered last year (Malus baccata), this year’s rootstock was tiny and we were left trying to figure out how we were going to graft it because on average, our scion is larger in diameter than above the root collar. That’s when I settled on the idea of root grafting.

This is a larger example of a the M. angustifolia crabapple we received from Maryland.

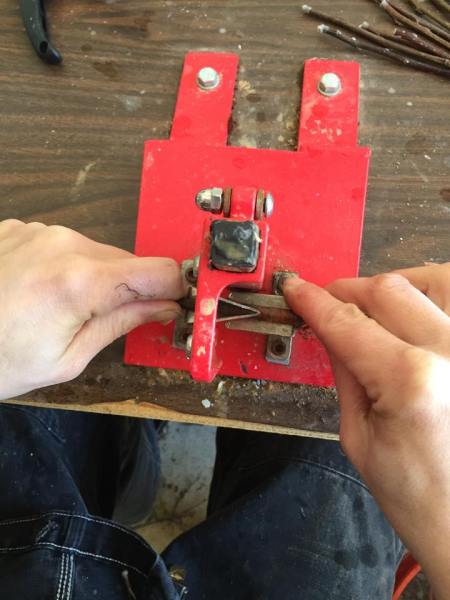

I use a foot powered saddle grafter much of the time to save my hands because I battle carpel tunnel due to repetitive orchard/nursery movements combined with being on the computer too much of the time.

This is what we’ve done to many, many crabapple trees. We took the root, made a grafting cut (some whip and tongue, many saddle, some omega and some cleft). Roots are often difficult for me to graft because many of them aren’t straight, but squiggly. This is where the saddle grafter came in handy, or we employed the cleft graft.

We left the scions larger when grafted. Usually, you only need a bud or two for grafting but I decided to leave 5-6 buds for reasons I’ll tell you about later in this post.

\

\

Pictured above is the final product. We grafted the scion to the root, wrapped it with a rubber band to make sure the union was nice and tight, and then wrapped the graft union/rubber band in parafilm (wax tape) from top to bottom. Some of you might be thinking: A rubber band PLUS parafilm! That’s overkill! And it is, to an extent (though it is pretty much a guaranteed take if you are able to make your vascular cambiums line up). But here’s why we did it…

By itself, horticultural rubber bands will degrade in the sun and fall off the tree within a certain time period so you don’t have to worry about it girdling the tree. By itself, parafilm will also degrade/expand/drop off a tree later in the season without it girdling the tree. TOGETHER, however, your tree is doomed for girdling unless you manually get out there in the summer and cut it off in time. I learned this the hard way, folks.

Why are we using this rubber band/parafilm method for grafting a root when I won’t be able to cut it off due to it being buried in the soil? Well- the answer is this: I want the girdling. Before I put this all together for you, I need to go on a brief tangent (which connects, I promise).

Last summer, we visited with Jason Bowman of Horne Creek Historical Farm (one of the sites that has Lee Calhoun‘s entire collection) and he was kind enough to take us through the orchard. Every year, I notice something different about trees and during this particular visit, I noticed how tree form differs from cultivar to cultivar. This is nothing new, really, because I’ve pruned many different cultivars of apples and they are all different. But this time, my knowledge of what trees had better disease resistances combined/confirmed with Jason’s were overlayed with tree form. I started to notice how apple varieties like the Dula Beauty naturally had wide crotch angles, creating better natural airflow and therefore, less fungal problems because humidity wasn’t being trapped within the tree as readily as some other varieties.

Keeping this in mind, I’ve been wanting to return my most disease resistant cultivars with excellent tree form (wide crotch angles) to growing on their own roots because I think they will require less pruning down the road (which is one of the big arguments for going to smaller trees…less and faster pruning). I want to see what size these trees will be without interference of rootstock, how many bushels of apples these trees will bear, and I want to taste an apple on it’s own roots as compared to another rootstock. That’s why we’re grafting in a way which will eventually have the root girdled from the scion (by using the rubber band/parafilm method). Alone, it’s fairly difficult for an apple cutting (scion) to produce roots on it’s own, so that’s why we’re grafting it to the crab roots. I want this crab stock to be a nurse to the scion, keeping the scion alive and fed while it starts to produce it’s own roots, and then to die off!

We left the scions long on these roots (5-6 buds rather than 2-3) to give room above the graft union to plant the scion. We’re going to try out two methods for this:

1.) We’re going to plant the whole thing and leave 2-3 buds sticking out of the ground. There will be irrigation.

2.) We’re going to plant the root and the graft union, and then cover the soil with several inches of sawdust which will be under irrigation. The area where damp sawdust contacts the scion should encourage root growth into that space.

When the time comes for digging these trees up and transplanting them, in a year or two, we may cut off the crab root if it’s still attached and alive. We’ll see! Updates to follow whenever we dig these things up (starting in the winter of 2016/2017).

Would the scions root better if you knocked the buds off that will be underground just before you planted them to stimulate healing cells to get going sooner? Your articles are always well written and fun to read, now I want to get some apple seeds seeds to grow my own rootstocks to do some rootgraftng! Jack inWV

It’s possible, Jack! We’re going to rub off a few low-down buds on certain trees and compare them with trees left to have their buds buried. We’ll see!

Great stuff as usual. I like the way you think (and that you do 🙂 I think there is a future for apple trees straight from cuttings as well. It is uncommon, but I keep hearing about people doing it, sometimes by accident. Clearly some varieties have a much higher propensity for rooting. My friend on a whim stuck in a row of pink pearl cuttings and they all rooted. Another lady I know on the coast here says she uses her apple prunings (might be yellow bellflower?) as garden stakes and they root all the time. If we paid attention or tested rootability over time, it might be that certain cultivars could be rooted without even resorting to root grafting. Those could also potentially be stooled just like clonals. What about an own root nursery using a combination of methods? Interesting possibilities. Then there is the tap root issue…

I think I have always assumed that root cuttings were used out of convenience. It’s easier and/or cheaper to dig up a root and graft it than to grow out seedlings for a year first. Maybe not so much if you choose certain roots. Haven’t I read somewhere that N. Spy was used for woolly aphid resistance? People worry here about woolly aphid a lot, and that would be an argument for clonal stocks, but there are many old trees that are obviously on seedling stocks or rootgrafted and seem to be just fine. I’ve been meaning to try out root grafting for years, just because. I’ll be looking forward to your results, whatever they are.

Love this idea!

I am working on a smaller scale, but have been experimenting for the past several years with planting smaller purchased nursery apple trees with their grafts below the soil. I have also done this with several other types of fruit trees. So far I have been impressed with the vigor of these trees (all have survived). I have also noticed these buried graft trees don’t ever send up suckers from the rootstocks. I always felt like there was some level of frustration (if such a thing is possible) at play for grafted trees, with the endless suckering these trees tend to do.

I have also experimented with burying grafts on already planted trees by top dressing with heavy loads of barn litter. This seems to have the same effect-vigorous tree, no suckers. I am experimenting this spring with grafting scions onto crabapple seedlings growing in my front yard. Again, I plan to cover or bury the grafts of the trees that take. Thanks for the help getting started with that, btw! I am also experimenting with apple cuttings that have been in a rooting bed in my front yard this past winter and spring. So far everything is alive-we’ll see what happens next.

I have also noticed, driving around my area, that the most prolific trees tend to be the huge, old fruit trees, abandoned and forgotten in a field, or bird planted seedling trees that pop up in little crevices here and there and fruit with no one really noticing. I am happy to plant my own-roots apple trees and then mostly forget about them while I do lots of other things, like grazing sheep, making cheese, spinning wool, etc!

Yeah Lisa! Thank you for chiming in!!! I’d love to send you guys some root grafted trees next year.

We’d love that too! 🙂

What is it that makes standards take so long to fruit? Is it something in their DNA or is it the way we plant them?

If seedling root stock is used you don’t really know what you are getting some could be monsters others bonsai but using seedlings as a root stock seems to work for high density plantings and is cheaper than buying dwarf root stock. Might take a bit more pruning but works. Is the reason that seedling root stock can work in a high density planting because of the density? The crowding effect causes them to fruit earlier?

What if we aimed for an orchard of standards but treated it like a forestry plantation? High density grid planting with un-grafted seedlings on 1.25m grid. With desired orchard standards on a 10m grid. As the trees mature take out successive rows and colums of ungrafted seedlings so that you go from a 1.25m grid to 1.25m x 2.5m grid, to a 2.5m x 2.5m grid, to a 2.5m x 5m grid, to a 5m x 5m grid, to a 5m x 10m grid to finally you are just left with the desired orchard on a 10m x 10m grid. Would that promote early fruiting of the orchard stock?

Would it be worth planting more grafted stock then the 10m grid? Maybe orchard stock on a 5m grid with three un-grafted seedlings between each tree on the 5m grid? Would it be worth planting denser with grafted trees and then thinning?